Max Gimblett’s Calligraphic Wonders

MARCH 16, 2023

by Mark Van Proyen

New York-based Max Gimblett was amazingly productive during the past three years of pandemic-related quarantine, so much so that the 18 paintings presented in this exhibition titled The Beginning of Time, are only a portion of a larger body of related works being unveiled over the course of three overlapping installations. The second, subtitled Spring into Summer, represents the latest iteration of this still-evolving show. Among many things, the 87-year-old artist is a Buddhist monk of the Rinzai school, the oldest of the three branches of Japanese Zen, suggesting that the different versions of this exhibition allude to the transitory nature of experience shaped by the notions of impermanence and non-attachment.

Of all the Japanese and Korean schools of Zen, Rinzai is most closely related to Mahayana sources from India, drawing much from China’s Ch’an tradition. These sources are all revealed in Gimblett’s paintings, even as they also reflect and embrace aspects of Euro-American Modernism (Gimblett briefly studied at the California School of Fine Arts in the early 1960s, just before it changed its name to the San Francisco Art Institute). Examples of such an east/west synthesis were common in the Euro-American painting during the second half of the last century, exemplified by Mark Tobey, Sam Francis, James Brooks and Gordon Onslow Ford. Gimblett’s paintings, however, reach deeper into the anti-dialectical metaphysics of Buddhism, far more so than the works of his many predecessors. At the same time, they are far more ebullient, disarmingly so, seemingly unbothered by anxieties bred from the pandemic, impending global war and economic chaos. Their cheerfulness seems buoyant and uncanny.

Half the works on view in this second hanging are executed on supports configured as four-lobbed quatrefoils, looking like overlapping venn diagrams based on the intersection of four cardinal circles. The Return, executed on a similar configuration of six circular lobes, echoes the sacred geometry of the Yantra or perhaps the Qabalah. All come across as devotional objects dealing with the dissolution and reconstitution of the ego, undermining the fear and desire-oriented monkey mind that makes an ego seem necessary.

Gimblett employs unusual materials and techniques, most notably metallic pigments and gilding to convey devotional purposes. Some, such as The Golden Cathedral and The Golden Bay, feature tiled applications of gold leaf covered with a layer of transparent epoxy that refracts the ethereal luminosity of the underlying material. Half of the quatrefoil form is similarly covered in True Mirror, while the others sport gestural applications of red and blue acrylic paint. In The Door to Paradise, Gimblett applies platinum leaf onto a circular tondo treated similarly. In Coral, he uses palladium leaf as a gestural shape to enliven a sumptuous field of rose magenta.

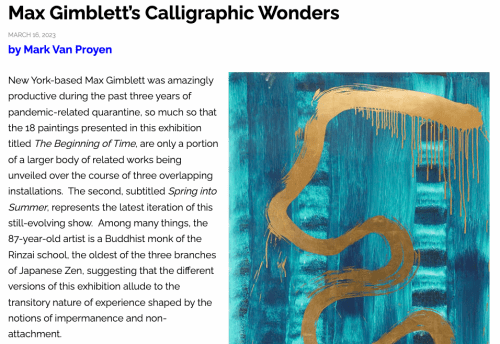

Most of the works in this exhibition feature gestural applications of brightly colored acrylic paint; it ranges from broad sweeps and flows of diluted pigments to precise calligraphic forms that suggest articulations of traditional characters. In truth, they are not, but the fact that they prompt us to think otherwise is to their credit. Even if the calligraphic gestures are only that, they still function as proxies for figurative signification because of how they are articulated and the positions they occupy relative to other aspects of the paintings. Gimblett sometimes applies these marks to the front of the epoxy surfaces, implying separation from the colors behind it. The effect is of suspended dance moves in a cosmic shadow play, like the “lifelines” (lightning bolt-like shapes) seen in paintings by Arthur Dove and Clyfford Still.

Maybe the most crucial point about the calligraphic aspects of Gimblett’s works is that their painterly qualities have much more to do with the esthetics of Asian art than with Euro-American proclivities. Gimblett purposefully changes the speed and force of his gestures in ways that give them a serpentine quality, coiling and uncoiling their way into and out of their containing picture spaces. In that way, they exemplify the “bone method,” one of the six ancient principles of traditional Asian calligraphy. It refers to forceful gestures, made without being brittle, lyrical or lapsing into visual mush. What we see in Gimblett’s work is a balance of opposites, revealing effortlessness that is the consequence of long years of practice.